Today, the term “genius” is bandied about to describe pop stars, stand-up comedians, and even footballers. But Leonardo da Vinci earned the description, explains Walter Isaacson in his lavishly illustrated new biography of the great Italian artist. From iconic paintings—“Mona Lisa” and “The Last Supper”—to designs for flying machines and ground-breaking studies on optics and perspective, Leonardo fused science and art to create works that have become part of humanity’s story. [Find out what science tells us about geniuses.]

When National Geographic caught up with Isaacson by phone at his home in Washington, D.C., he explained why Mona Lisa’s smile is the culmination of a lifetime of inquiry; how Michelangelo and Leonardo couldn’t stand each other; and why being curious was Leonardo’s defining trait.

We have to start with the most famous smile in the world. Where does the “Mona Lisa” fit into Leonardo’s life and work—and how has she managed to bewitch us for 500 years?

The Mona Lisa’s smile is the culmination of a lifetime spent studying art, science, optics, and every other possible field that he could apply his curiosity to, including understanding the universe and how we fit into it.

Leonardo spent many pages in his notebook dissecting the human face to figure out every muscle and nerve that touched the lips. On one of those pages you see a faint sketch at the top of the beginning of the smile of the Mona Lisa. Leonardo kept that painting from 1503, when he started it, to his deathbed in 1519, trying to get every aspect exactly right in layer after layer. During that period, he dissected the human eye on cadavers and was able to understand that the center of the retina sees detail, but the edges see shadows and shapes better. If you look directly at the Mona Lisa smile, the corners of the lips turn downward slightly, but shadows and light make it seem like it’s turning upwards. As you move your eyes across her face the smile flickers on and off.

He carried his notebook around as he walked through Florence or Milan, and always sketched people’s expressions and emotions and tried to relate that to the inner feelings they were having. You see that most obviously in “The Last Supper.”

But the “Mona Lisa” is the culmination because the emotions that she’s expressing, just like her smile, are a bit elusive. Every time you look at her it seems slightly different. Unlike other portraits of the time, this is not just a flat, surface depiction. It tries to depict the inner emotions.

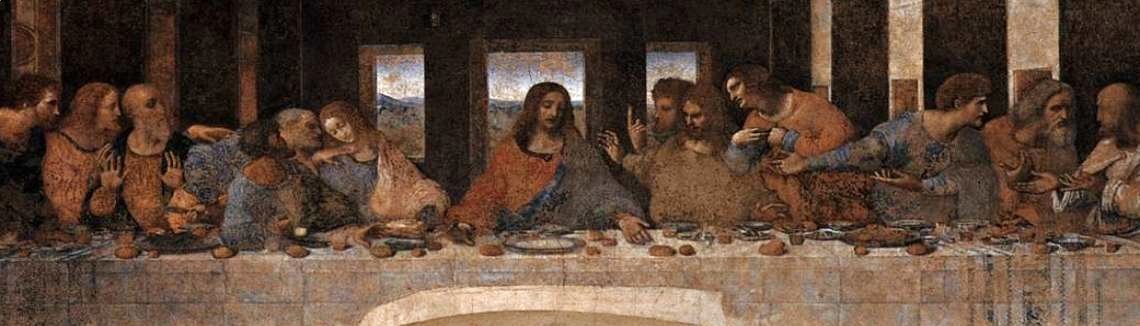

His other most famous masterpiece is “The Last Supper,” which you call “the most spell-binding narrative painting in history.” Take us inside its creation—and explain why it is such a supreme work of art.

The Duke of Milan asked him to paint it on the wall of a dining hall of a monastery. Unlike other depictions of “The Last Supper,” of which there were hundreds at the time, Leonardo doesn’t just capture a moment. He understands that there is no such thing as a disconnected instant of time. He writes that any instant has what’s come before it and after it embodied into it, because it’s in motion.

So he makes “The Last Supper” a dramatic narrative. As you walk in the door, you see Christ’s hand then, going up the arm, you stare at his face. He’s saying, “One of you shall betray me.” As your eyes move across the picture, you see that sound almost rippling outward as each of the groups of apostles reacts.

Those nearest to him are already saying, “Is it me, Lord?” The ones further away have just started to hear it. As the drama ripples from the center to the edges, it seems to bounce back, as Christ reaches for the bread and wine, the beginning of what will be the institution of the Eucharist.

Despite these achievements, in his own day Leonardo wasn’t primarily known as a painter, was he, but as an architect—and even what we would today call a special effects guy. Unbraid these different strands of his life.

He was mainly, despite what he sometimes wished, a painter. He liked to think of himself as an engineer and architect, which he also did with great passion. But his first job was as a theatrical producer.

From that he learned how to do tricks with perspective because the stage in a theatre recedes faster and looks deeper than it is. Even a table onstage would be tilted slightly so you can see it, which is also what we see in “The Last Supper.” Likewise, on the stage, the theatrical gestures of the characters would be exaggerated, which is what you also see in “The Last Supper.”

His theatrical production led him to mechanical props, like flying machines and a helicopter screw, which were designed to bring angels down from the rafters in some of the performances. Leonardo then blurred the line between fantasy and reality when he went on to try to create real flying machines that were engineering marvels! So, what he picked up in the theatre he brought both to his art and real-life engineering.

What about Leonardo, the man? He was a vegetarian and openly gay, in an age when sodomy was a crime, and quite a dandy. Unpack these different aspects of his character.

He was gay, illegitimate, left handed, a bit of a heretic, but the good thing about Florence was that it was a very tolerant city in the 1470s. Leonardo would go around town wearing short, purple and pink outfits that were somewhat surprising to the people of Florence, but he was very popular. He had an enormous number of friends both in Florence and Milan. He records many dinners with close friends, who were a diverse group: mathematicians, architects, playwrights, engineers, and poets. That diversity helped shape him.

Finally, he was a very good-looking guy. If you look at “Vitruvian Man,” the guy standing nude in the circle and square, that’s largely a self-portrait of Leonardo with his flowing curls and well-proportioned body.

There was a well-known, and mutual, dislike between Leonardo and Michelangelo. Explain the animosity—and set the scene for what became a kind of painterly “high noon” between them.

Leonardo and Michelangelo were very different. Leonardo was popular, sociable, and comfortable with all his eccentricities, including being gay. Michelangelo was also gay but deeply felt the agony and the ecstasy of his identity. He also was very much of a recluse. He had no very close friends, wore dark clothes, so they were polar opposites in look, style, and personality.

They were also very different in their art styles. Michelangelo painted as if he were a sculptor, using very sharp lines. Leonardo believed in sfumato, the blurring of lines, because he felt that was the way we actually see reality.

The rulers of Florence created a competition for both of them to paint battle scenes in the Council Hall. By that point, the rivalry had become bad.

Leonardo had voted to have Michelangelo’s statue of David hidden away in some arcade rather than placed in the middle of the plaza. Michelangelo had been publicly rude to Leonardo. All of this had caused a certain electricity, so the rulers of Florence pitted them against each other to do these two battle drawings.

In the end they both flinched, quitting before they finished the paintings. Then Leonardo moved back to Milan and Michelangelo moved to Rome to work on the Sistine Chapel.

Leonardo never signed his paintings, which has sometimes caused confusion. Tell us the amazing story of “La Bella Principessa”—and the Sherlock Holmes-type investigation to establish its authenticity.

“La Bella Principessa” is a chalk drawing that turned up at auction a few decades ago. It was never thought to be a Leonardo, and sold very inexpensively because they thought it was a German copy of a Florentine artist.

But one art collector was convinced that it was an authentic Leonardo. He bought it and took it around the world to experts to determine whether it truly was a Leonardo. It was pretty much confirmed when they found fingerprints because Leonardo often smudged his work using his thumb.

Then it turned out that the guy who made that claim was a bit unreliable and perhaps even fraudulent so the claim was withdrawn. Finally, with the help of Martin Kemp, the great Oxford Leonardo scholar, they discovered that it was a drawing made by Leonardo, which had been the front piece of a book that was in a library in Poland where somebody had cut it out.

More recently, we have the tale of Salvator Mundi, a beautiful painting that goes on sale November 15th at Christies. For a long time, we also thought this was a copy but in the past ten years it’s been authenticated. It was sold a decade ago for about $100. In November, it’ll probably go for more than $100 million.

It’ll be a major event because it’s the only Leonardo painting in private hands. Nobody will probably ever be able to buy a Leonardo painting again.

One of the natural elements that most fascinated Leonardo, and to which he returned at the end of his life, was water. What did he see in it?

He was a self-taught kid. He didn’t go to school because he was born out of wedlock and among the things he loved was the flow of the streams that went into the Arno River. He studied those, and from his childhood to his deathbed, he was still drawing the spiral forms and trying to figure out the math behind them.

That translates both into a science and his art. He loved how air currents formed little flurries when they went over the curved wings of birds and realized that they helped keep the bird aloft, something we now know about airplanes.

In any of his masterworks, including the “Mona Lisa,” you see a winding river, as though it connects to the blood veins of the person in the portrait, like a connection of the human to the earth.

What do you think is the defining trait of Leonardo’s genius? And what can he teach us?

In the last chapter, I try to answer that with 25 lessons from Leonardo, that also distill lessons from previous books I’ve written on Steve Jobs or Albert Einstein. In all those books, I’ve noticed that creativity comes from connecting art to science. To be really creative, you have to be interested in all sorts of different disciplines rather than be a specialist.

The ultimate example of that is Leonardo da Vinci, who is interested in everything that could possibly be known about the universe, including how we fit into it. That made him a joyous character to write about.

In his notebooks, we see such questions as, describe the tongue of the woodpecker. Why do people yawn? Why is the sky blue? He is passionately curious about everyday phenomenon that most of us quit questioning once we get out of our wonder years and become a bit jaded.

Being curious about everything and curious just for curiosity’s sake, not simply because it’s useful, is the defining trait of Leonardo. It’s how he pushed himself and taught himself to be a genius. We’ll never emulate Einstein’s mathematical ability. But we can all try to learn from, and copy, Leonardo’s curiosity.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment